Writers create national literature but translators create world literature.

A Booker Moment For Marathi Literature Is A Pipedream

The rich world of Marathi literature has been greatly let down by translators who lack creativity and publishers who lack conviction

—Jose Saramago

Years ago, when writer Gurunath Naik wanted some of his Marathi fiction and non-fiction boo-ks translated into English, he approached a vast pool of people, seeking help for his project. These included journalists, newspaper feature writers, Marathi teachers and others. Though some of them did evince some interest in it, none followed up when they realised it wouldn’t be a profitable proposition. Naik’s wish remai-n-ed unfulfilled. He passed away some years ago, taking with him the dream to see the English version of at least one of his books. A prolific writer, today his books are no longer available in the public domain.

This is the story of many Marathi writers seeking a pan-Indian and international audience for their books of fiction, non-fiction, biography, autobiography, short stories and poetry.

Marathi literature is a challenge for tra-n-slators, particularly into English, say publishers who spoke with Outlook. The challenge is to keep the original idiom and express the meaning in a manner in which the reader of the translated work would und-erstand, they say. They also agree that Marathi literature is limited by geographical boundaries due to a lack of translations. “Un-l-ess the works are translated into Eng-l-ish, the rich literature won’t reach the global reader,” says Rohan Natekar, an independent translator.

The Marathi publishing industry is unable to attract skilled translators as it is not com-me-r-c-ially viable. Most translators are paid much less than the writers. The hap-hazard substitution of English words for Marathi ones has become a textual irritant that often mars the quality of translations, said a source. Besides, translation of Marathi to English is not considered commercially viable by either the publishers or the retailers, as profits are little. Another major problem is the flood of low-pri-ced books in the market, which has given lit-erary titles tough competition for shelf space in book stores. Retailers consider translated Mar-athi works to have a shorter shelf life due to lack of readers and lack of promotions for such works.

Internationally well-known painter and wri--ter Prakash Bal Joshi laments the present state of the Marathi publishing industry. Spe-aking to Outlook, he points out that translations cannot be a mechanical process. “The translator has to be involved and must understand the original work, without which it can’t be done. When someone is translating a poem, story or other literary work, you are translating the ethos of the people, aspirations and much more. You are translating one culture to another,” says Joshi. According to him, translation is an important aspect for knowing people, their cultures, their beliefs, etc.

“Marathi literature has high standards. When you translate Marathi into another language, you are enriching Marathi, as the translated work will find new readers. In comparison to the other regional languages, there are fewer Marathi works being translated into English. Marathi publishing is in dire condition as they have to compete with digital publishing and e-books. When the original Marathi literary works are not finding buyers, who will buy their translations?” asks Joshi. His collection of short stories in Marathi, Prakash Bal Joshi Hyanche Katha, has been translated into Eng-l-ish as Mirror In The Hall. The original collection is also being translated into Gujarati, Hindi, Malayalam and French.

Humour in Marathi is the most difficult to translate, say many publishers. Translators cannot find adequate English alternatives while translating puns, cultural context, proverbs and social references. “The essence of humour is lost when trying to translate it,” says Natekar. One of the most popular humourists in Marathi, P.L. Deshpande—known as the Marathi P.G. Wodehouse—had often said that his works would be the toughest to translate. There are many who have tried translating Deshpande’s works but the results are disastrous. “I have junked some works that were translated by a well-known translator. The attempt was dismal, with the essence of Pu La’s (Deshpande) humour completely lost,” says Deepali Rane, who works at a publishing house.

Yashodhan ‘Yeshu’ Patil, proprietor of Shabd Publication, has been publishing Marathi lit-erature since 2004. Among the 150 titles published so far, three have won the Sahitya Akademi, while three others have been awa--r-ded the Yuva Akademi awards. Though his publishing house has brought out books by a number of well-known Marathi authors and poets, they are taking baby steps in the translation of Marathi books into English and other regional languages. “It is difficult to translate Marathi into English or other languages primarily because there are no good translators proficient in both languages,” says Patil to Outlook. “The translated version must have a life different from the original, while keeping the essence intact. Translators are looking at a word-to-word translation, not of the essence. Unless translators and authors speak to each other, it’s difficult to get to the essence,” he adds.

Publishers deplore the skills of existing translators, barring exceptions, and feel they do not take their trade seriously. “For a majority, translation is a side income. There is a dire need for trained translators who will translate keeping in mind the tonality of the writing,” says another publisher.

“In Marathi, there are gendered nouns like night, river, dawn and dusk, which are all feminine, but when translating it into English, they become gender neutral. So much gets lost in translation,” says the publisher, who has withdrawn translations due to the shoddy quality of work. “It consumes time and money, and publi-shing deadlines go haywire,” the publisher adds.

The first decade of the 2000s was considered to be the golden era for thr Marathi pub-l-i-shing industry. There were many publishers who spe-cialised in tra-nslated works and a number of Marathi books got translated into English. Without a sec-ond thought, publishers had then put out print runs of 2,000-3,000 copies per title, in both fiction and non-fiction categories. There were numerous book fairs held in big cities, towns and even smaller places, and people bought Marathi books including translations, says a bookseller. However, the past decade has seen the decline of the Marathi publishing indus-try, with demonetisation, GST and Covid-19 slowing it down.

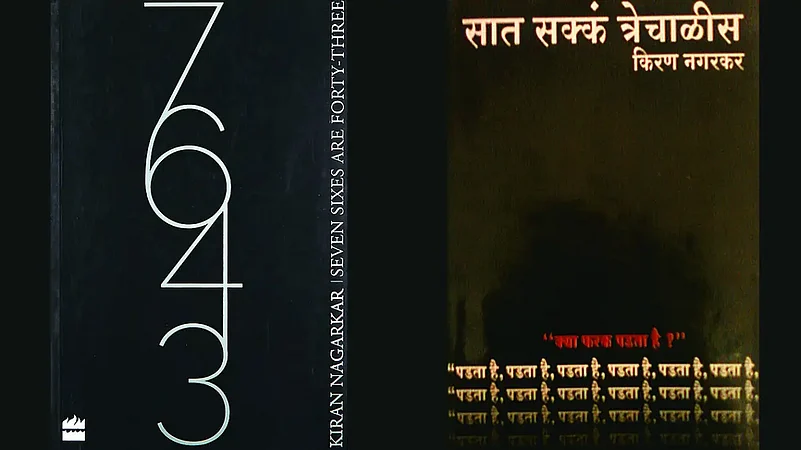

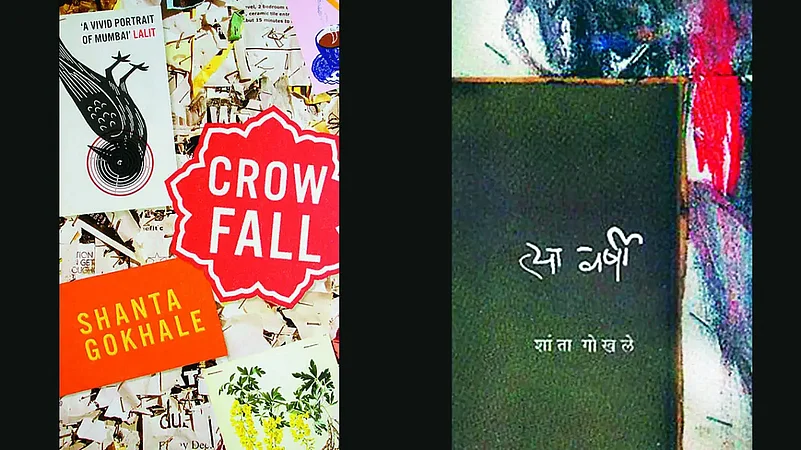

On the international front, there are some who have picked up the gauntlet to promote Marathi literature through translated works. Ian Raeside, a lecturer in Marathi at the University of London, has translated a collection of modern short stories written by Gangadhar Gadgil, Arvind Gokhale, P.B. Bhave, Vyankatesh Madgulkar, D.B. Mokashi, D.M. Mirasdar, Maltibai Bedekar and others, titled The Rough and the Smooth. Raeside has also translated the book Garambicha Bapu by S.N. Pendse as The Wild Bapu of Garambi. Shubha Slee has, meanwhile, translated Kiran Nagarkar’s first book, Saat Sakkam Trechalis, into English in 1995 and published it as Seven Sixes Are Forty-three, while Sudhakar Marathe translated Bhalchandra Nemade’s novel Kosla into English as Cocoon for Pan Macmillan India. Penguin India published Crowfall, the English translation of Shanta Gokhale’s Tya Varshi.

“There has to be an aggressive promotional strategy for translated works from Marathi to English, as it is the power window to the world. The irony is that not many Maharashtrians are reading Marathi literature,” says Joshi. Interestingly, the loss of readership for Marathi literary works has been a gain for Hindi literature in the Marathi-speaking world. “The emerging trend is that many Maharashtrians have switched to reading Hindi literary works and given Marathi a go-by. This is also pushing Marathi readership down,” says Patil.

Many in Marathi literary circles point out that Marathi departments in various universities across Maharashtra have failed to play the central role in assisting the growth of Marathi literature and its English translations. According to Dr Aruna Rege, a professor of Marathi, “Marathi departments must motivate students to undertake the work of translating Marathi literary works. The students need guidance and stimulation to embark on it,” says Rege to Outlook. “If the rest of the country has to look at literary works in Marathi, they have to be made aware of it through translations. A demand has to be created for the translated Marathi literary works,” says Rege.

Presently, there is little funding for commissioning translators, as a result of which, the field is unable to attract skilled translators. The main reason for fewer translated works from Marathi to English is because it is considered a “tricky domain”, say publishers. However, numerous books from non-Indian languages have been translated into Marathi, and they have had a better run than original Marathi titles or translations into English or other regional Indian languages.

For those with Marathi as their mother tongue and a functional grasp of English, translating into Marathi is possible. However, the available pool of translators with adequate writing skills in English is not too impressive, say sources. “The ongoing problem with translators is that they do not have the creative skill to translate fiction, poetry, etc. It is not just a word-to-word translation. The specialised skill and proficiency is in short supply,” says a well-known writer who has been looking for a translator to publish his works in English.

“Publishers are not even bothered about translations. They are more worried about selling the original. Marathi publishers need a little more aggression and sophistication in the promotion of our books,” the writer adds.

Though writers have been seeking specific imprints for translated books, barring a small number, not many publishers have responded. “There is a bitter divide between English and regional writers. Unless Marathi writers and translators talk to each other, they won’t be able to establish a rapport. The translator has to understand the book, the story, the characters and its essence. Only then can the translation have a life of its own,” says Patil.

(This appeared in the print edition as "A Popular Refrain")

Haima Deshpande in Mumbai