When Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was preparing its bid for West Bengal ahead of the 2019 Lok Sabha election, a senior BJP ideologue told this writer that the party hoped Mamata Banerjee’s rise in West Bengal politics had shattered the Bhadrolok dominance over the state’s socio-cultural sphere, making it easier for the BJP to make inroads into the state. “The Bhadrolok who take pride in their secular-liberal views have been the biggest hurdle towards our mass acceptance in Bengal,” said the ideologue. “But Banerjee’s rise has meant the subalterns have gained the upper hand over the Bhadrolok.”

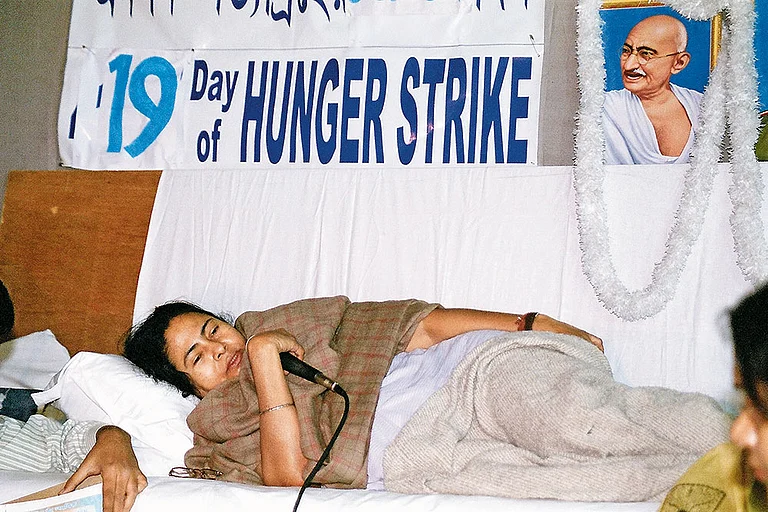

West Bengal Elections: What Is Mamata Didi’s Achilles Heel?

Mamata Banerjee stays the course but her party, plagued by corruption charges, spins out of control

The Bhadrolok are the English-educated, mostly Hindu upper-caste, upper and middle-class elites who have dominated the discourse in the state from pre-Independence times. Culture is integral to Bhadrolok society. Children in Bhadrolok families are usually trained in painting, poetry recitation, singing, dancing, playing musical instruments, or several of these arts. Born in a lower-middle-class family, Banerjee grew up without any of these. In the Bhadrolok-Chhotolok (subaltern) divide in Bengali society, Banerjee belonged to the latter.

Considered by many to be loud and theatrical, Banerjee became an ideal element for Jatra, a form of Bengali folk theatre. Cultural elites look down upon Jatra for its lack of artistic refinement, but the form enjoys immense popularity in Bengal’s rural districts. In the 1990s, when she was becoming known as Agnikanya or daughter of Fire, Banerjee’s detractors often referred to her as bostir meye (slum woman) or kajer mashi or jhi (domestic help) in informal conversations. Her All India Trinamool Congress (TMC) was considered “Congress minus its Bhadrolok” right from its inception in 1998.

According to political scientist Ranabir Samaddar, Banerjee had to face the sneers and snubs of the political class all through the 1990s and the following decade “because she was not ‘respectable’. She was a commoner and had no trait that showed marks of wealth or birth.” To many, it came as a culture shock when Bengali filmstar Dev performed his Palgu Dance moves from one of his blockbuster movies on the dais of Banerjee’s party’s flagship event—Martyrs’ Day on July 21, 2011—the first edition after the TMC came to power. Dev is now running for a third term in the Lok Sabha. Shatabdi Roy, another Bengali filmstar, is eyeing her fourth term.

During Banerjee’s rule, the Kolkata International Film Festival has seen Bollywood stars’ presence dwarfing those of international figures of arthouse cinema. The festival was originally meant to promote and popularise cinema that is hard to find in the threatres. But Banerjee’s audience loves Amitabh Bachchan, Rajnikanth, Mithun Chakraborty, Prosenjit and Dev. So, she has turned the inauguration of the festival into a Bollywood event. Anti-elitism has been part and parcel of her politics. She speaks of TV soaps at public functions and her government gives awards to TV stars.

Banerjee’s rule also saw an increase in Hindu lower caste and non-forward or intermediate caste representation in political leadership at different levels, according to an unpublished research paper by Kolkata-based political scientist Zaad Mahmood and Bengaluru-based researcher Soham Bhattacharya. Her party fielded Scheduled Caste (SC) candidates even from non-reserved seats and had a higher prevalence of intermediate castes from general seats.

However, the BJP ideologue’s hope of waning Bhadrolok influence in Bengal’s political sphere did not come true. In the 2019 Lok Sabha election, Kolkata and its neighbouring districts in south Bengal—where the majority of the state’s caste Hindus live—remained Banerjee’s strongest bastion. The party lost its grip on the state’s northern and southwestern parts, where the majority of the state’s backward communities live, to a saffron surge. It’s the non-elites who first dealt her a blow.

“The Bhadrolok want stability. She has given Bengal political stability,” says a TMC Rajya Sabha MP who does not wish to be named.

Since coming to power, Banerjee tried to create a social base among the poor with a chain of welfare schemes.

Even in the 2021 assembly election, Gangetic south Bengal where the Bhadrolok predominantly live, returned the BJP almost empty-handed, except for the areas dominated by lower-caste Hindu migrants from eastern Bengal. According to Maidul Islam, a political scientist at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta (CSSSC), the liberal Bhadrolok mostly aligned with the Left and the conservative Bhadrolok stood with the Congress during the 1980s and 1990s. Banerjee and her party’s initial base was the ‘lumpenproletariat’ in the urban areas and the rural rich in the villages.

While the Left leadership was dominated by the sophisticated middle-class cultural elites, who were largely patriarchal and treated women patronisingly, Banerjee was a sharp contrast: the ‘kajer mashi’, the ‘bostir meye’.

“However, her party has since transformed into a mass party following the anti-displacement movements in Singur and Nandigram (2006-08) and the Bhadrolok society has developed confidence in her rule,” says Islam. He adds that the TMC has always been largely an urban and suburban party though its support base was outside the Bhadrolok class. “Currently, the TMC’s grip on the Bhadrolok is finding its legitimacy,” he adds.

But as ‘Didi the Ruler’ consolidated her support among the socially influential class, especially among the intelligentsia and the civil society, the BJP grew in the rural hinterland. The Lokniti-CSDS post-poll surveys of 2019 and 2021 reveal the BJP’s rise was more due to an anti-corruption wave than a pro-Hindutva one. The TMC’s apparent mal-governance and corruption had possibly allowed the BJP the space to sell Hindutva.

Since coming to power, Banerjee looked to create a social base among the poor with a chain of welfare schemes, particularly targeting women and farmers. Direct benefits schemes, self-help groups, maternity benefits, health insurance, old-age pensions and student scholarship schemes remain popular. She has consciously tried to avoid being seen as pro-corporate. Even as her party has emerged as one of India’s richest regional parties, she maintains her humble appearance and avoids glitzy events. In 2021, she refused to enter a party leader’s home in East Midnapore after seeing his palatial new building.

However, most TMC leaders are fond of displaying their newly accumulated wealth—from building imposing houses to flaunting expensive cars, watches and new properties. A large section of the intended beneficiaries of her government’s welfare scheme are upset with the level of corruption they have to deal with.

“Didi has not changed much but does she have any control over her party leaders? Does she not know about the nawabs and zamindars that we have to deal with?” asks Pintu Malo, a grocery shop owner at Habra town in North 24 Parganas district. The local MLA, Jyoti Priya Mullick, had been an influential TMC leader and minister until the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) arrested him for his alleged involvement in a public distribution system (PDS) scam. Mullick is the second heavyweight minister after Partha Chatterjee to land in jail since Banerjee’s historic return to power in 2021.

Perhaps such widespread, grassroots-level corruption has its roots in how the party was born—people having varying interests in dethroning the Left, not necessarily due to any ideological reasons, had gathered around her and her blindest followers became her closest aides. The 2006-08 anti-displacement agitation went well with her pro-poor, anti-elite image but her land policy also meant that she was not going to get much corporate backing in her party’s financial affairs. The party depended on the informal economy.

Mahmood and Bhattacharya’s research also recorded a shift in the economic background of the political representatives after Banerjee’s rise. During the Left Front regime, the salaried, self-employed professionals like doctors, lawyers, social workers and political activists dominated political representation. However, during the TMC’s rule, the salaried and the self-employed professionals have been replaced by those identifying themselves as businessmen.

Mahmood and Bhattacharya describe the ‘‘businessmen sector’’ as a “non-corporate commercial class” engaged in small-scale businesses like hotels, rice mills, transport, construction and real estate. Dwaipayan Bhattacharyya, a political scientist at Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), says that TMC leaders have “produced crony capitalism of a non-corporate variety.” Since non-corporate capital is mostly invested in the relatively small-scale informal sector involving myriad manufacturing and services industries, spoils of the profits get distributed among a larger number of people than in corporate cronyism.

As the political battle for 2024 peaks, the TMC remains worried about the impact of corruption and the highhandedness of its local leaders.

“The mix of politics and profit gives the TMC’s financial structure the flavour of cronyism. Yet, being of a non-corporate kind makes it mandatory for such enterprises to share the spoils with a larger number of clients,” Bhattacharyya tells Outlook. He points out that in corporate cronyism, political support is obtained directly from the top executives of the state. For non-corporate cronyism, the protective political shield has to come from the support of a large group of beneficiaries. While such local business networks may help the TMC maintain its political hegemony at the grassroots level, such a structure can also be the source of unrestrained corruption.

As the political battle for 2024 peaks, the TMC remains worried about the impact of corruption and the highhandedness of its local leaders. Sandeshkhali in North 24 Parganas presents a classic example, where the business interests of local leaders led to rampant land grabs. In the backward regions of West Bengal, where people’s awareness and empowerment levels are low, local leaders often take many corrupt practices for granted.

The situation has brought Banerjee face to face with a major challenge. A politician whose unique selling point (USP) was satotar protik (an embodiment of honesty) is now trying to fend off a series of corruption charges in government recruitment and welfare schemes involving her party leaders and the administration. Whether in urban or rural areas, in local self-governance or the state administration, people have complaints of corruption at every level. Her opponents are calling her “choreder rani” (the queen of thieves). “TMC leaders attribute every move of the administration to inspiration from her. How, then, is it possible that she did not inspire the corrupt practices?” asks Bengal Congress president Adhir Ranjan Chowdhury, one of Banerjee’s harshest critics.

Whether she can use her mass connect skills and the transactional value of her welfare schemes to hold on to her political dominance remains to be seen. It is the marginalised whose trust she must win once more to stay on in power.

Snigdhendu Bhattacharya in West Bengal

(This first appeared in the print as 'Didi's Achilles Heel')

- Previous Story

‘Staying Out Of Power Has Made Congress Desperate’: PM Modi Slams Rahul Over ‘Country On Fire’ Remark

‘Staying Out Of Power Has Made Congress Desperate’: PM Modi Slams Rahul Over ‘Country On Fire’ Remark - Next Story