The boy used to sell lampshades at Linking Road. He used to walk among the cars when they stopped at intersections and offered his merchandise to anyone who would listen. He made these shades with his own hands, he claimed. They were meticulously designed and came in a variety of bright, luminous colours. He sold them for Rs 25 a piece. The random passersby, who bought some of those lampshades, didn’t know who they were buying it from. That boy had grown up among Bollywood royalty and was soon going to shape the world according to his vision.

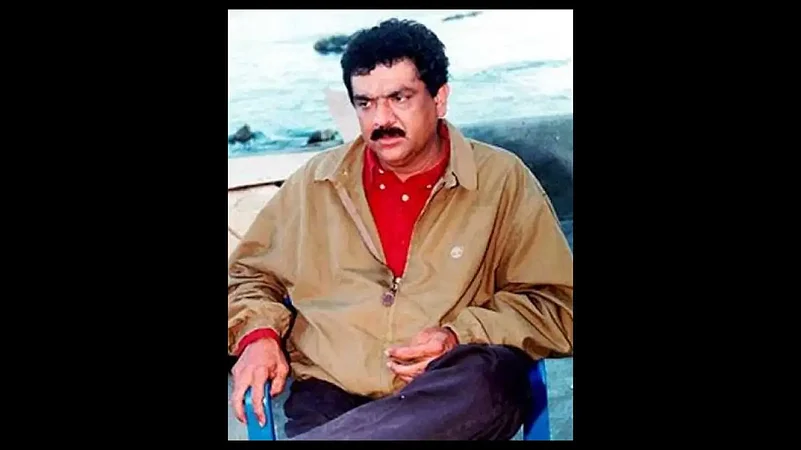

Sands of Time - Part 24: Mukul Anand - The Merchant of Really Large Things

Mukul Anand was MAD. It was the name of his company, and it was what his team called him. No filmmaker of his generation had the kind of sweeping, panoramic vision and grandeur that his cinema exhibited. In fact, Bollywood of the 90s was too small to fit the scale of his dreams.

Mukul Sudheshwar Anand’s father was a highly respected Chartered Accountant and tax consultant, who had as his clients some reigning stars of the fifties and the sixties. He used to throw grand parties on his son’s birthday, attended by Dilip Kumar, Mehboob Khan, the Kapoors, B.R. Chopra and his family, Harnam Singh Rawail, along with Mukul’s own contemporaries, little Dabboo and Chintoo Kapoor. Although this was not a family of filmmakers, cinema was lurking around. Mukul and his siblings grew up on a steady diet of films, both Indian and international. But by his own admission, Hollywood didn’t hold as much fascination for him as did the homegrown cinema of India. By the early 70s, Mukul was out of Mithibai College and the love of film was running in his veins but finally, it was compulsion and happenstance that led him to filmmaking.

Sudheshwar Anand was gravely ill, and Mukul had to take on the mantle of the breadwinner. Selling those lampshades brought in some quick buck. Mukul later said to V.S. Srinivasan, in an interview with Rediff On The Net, "When I came out of school, I realised I wanted to get into films. But there was no scope since my family was in a bad state and I couldn't become a struggler at that time. My father wasn't well and we needed the money. So I used to make and sell lampshades on Linking Road, Bandra. I sold stuff for Rs 25 then to earn a living. It was a very bad phase, and I can never forget it. I was happy I could put to use some of the skills I'd developed to feed my family."?But a more steady flow of income was necessary, and Mukul began to solicit work within the industry.

Maverick filmmaker Chetan Anand took him under his wings, and Mukul assisted him on Hindustan ki Kasam (1973). But eventually, it was Chetan’s brother Vijay aka Goldie Anand he happened to learn the most from. Mukul later said to Rauf Ahmed, “I learnt more from Goldie Anand, with whom I often discussed cinema, because Chetan saab seldom let anyone know what he was up to. He kept everything close to his chest, and gave us regular surprises.” After this brief stint, Mukul assisted Ravi Tandon (Raveena Tandon’s father) on films like Zindagi (1976), Muqaddar (1978), and Chor Ho Toh Aisa (1978). During this period, Mukul also came in touch with writer Dhruv Chatterjee, who had written classic thrillers like Woh Kaun Thi? (1964) and Gumnaam (1965). Mukul Anand’s vision had begun to take shape but wasn’t fully formed yet. A quick succession of ghost-directing projects ensued. For a meagre 100 or 200 rupees, he got used to ghost-directing Punjabi and Gujarati films. A film called Maa ki Saugandh came his way, but he couldn’t complete it. The title was ironic, as Mukul’s mother passed away on the first day of shooting. Today the film exists on YouTube, and the credits end with “Produced and Designed by Ravi Anand”, with no directorial credits whatsoever. A film called Sultan was conceived with Raaj Kumar in the lead, but the superstar wanted to direct all his closeups himself. Mukul Anand left Raaj Kumar’s house in a huff. Sultan, too, failed to take off.

It was a chance meeting with Amitabh Bachchan’s personal photographer Mehboob Alam that set the ball rolling. Alam took him to see his partner Bhagwanji Sindhwa, a jeweller who was ready to finance a film but wanted to see samples of Mukul’s work. So far there was nothing to show for, so Mukul’s friend Romesh Sharma offered a solution. He was about to star in a new Gujarati film, and Mukul could ghost-direct it if only to get a “sample” to show to Bhagwanji. The result was Kanku Ni Keemat (1983), a much-hyped spectacle with many Bollywood stars like Danny Denzongpa, Bindiya Goswami and Vinod Mehra making cameos. The film resembled Maa ki Saugandh from frame to frame. Bhagwanji Sindhwa was happy with the sample provided, and gladly furnished the money to Mukul Anand so that he could direct his first film, Kanoon Kya Karega (1984), an unofficial remake of Cape Fear (the J. Lee Thompson film. Martin Scorsese’s version was still 7 years away.) Film journalist Rauf Ahmed watched the screening in Dimple preview theatre and was bowled away by the technical finesse, which was to become the hallmark of Mukul Anand’s films. He sought out the director to compliment him on his work. Mukul said nonchalantly, “So you like Cape Fear in Hindi?”. He could have taken the praise and moved on. Rauf hadn’t even seen the original film. But Mukul Anand was, well, Mukul Anand.

?

The next project was also inspired, this time from Alfred Hitchcock’s Dial M for Murder. The idea for Aitbaar (1985) came from Danny Denzongpa and Romesh Sharma produced it. Mukul was "preoccupied with the presentation",?at this time. The film was shot almost entirely in a room, but it is Mukul’s slick filmmaking that never lets the claustrophobia kick in. It was only after Aitbaar that Mukul finally found the canvas he always wanted. Mukul Anand’s vision, like he proved time and again, was of an epic scale. His framing, panoramic visuals and the way he mounted his stars begged for a grand, epic scale. And that was allowed to him for the first time in Sultanat (1986), a high-octane actioner that unfolded in the desert, bringing Dharmendra and his son Sunny Deol together for the first time. But producer Arjun Hingorani had cold feet. He was intimidated by Mukul’s canvas and vision. The director and producer had a falling out, and the film suffered.

Mukul Anand followed this up with two Vinod Khanna crime capers, Insaaf (1987) and Maha Sangram (1990), both of which were testaments to Mukul’s signature style and vision. While being loud and shrill like most 80s films, they were also operatic. But what probably pulled Mukul Anand into the history books was the trilogy of films he made with Amitabh Bachchan. Though Agneepath failed at the box office, it had a massive impact and developed a cult following over time. Bachchan’s entry scene and monologues, Danny’s iconic Kancha Cheena, Mithun Chakraborty’s turn as Krishnan Iyer, and Master Manjunath as the young Vijay Chavan captured the audience’s imagination. The extent of detailing in that film was impeccable. Amitabh Bachchan bagged a National Award for his role, while Mithun got a Filmfare. Hum was such a complete departure from his role in Agneepath that Bachchan was himself a bit taken aback, especially with the song which still plays in pubs all over the world. The film had crossed the break-even point even before the first show went live. For the first time ever, more than 300 prints of a Hindi film were being released in 400-plus theatres. Hum was a sensation. Even with three of the biggest stars sharing the frame, Mukul found a way to be equitable. The scenes at the dock vibrated with energy and spectacle that was quite Mukul’s own. Every frame had the signature Mukul Anand vibe.

With Khuda Gawah, Mukul took it to the limit. He mounted it on a scale never before seen in the sub-continent. It was shot extensively in Afghanistan, with the sport of Buzkashi being featured in a Hindi film for the first time. The panoramic visuals and the expanse bring to mind the splendour of Lawrence of Arabia. With this one, Mukul had truly outdone himself. The film was a hit but didn’t generate the kind of craze they had hoped it would. While the Bachchan behemoth took Bollywood by storm in the 70s, his aura seemed to be diminishing by the late 80s and early 90s. It was the trilogy by Mukul that showcased the Bachchan magic anew and demonstrated that this giant of a star was still a giant. But Khuda Gawah took a toll on Mukul, and he stepped aside from the arclights for a while, concentrating on making ad films and working for television.

?

Mukul came back from the sojourn with renewed vigour, announcing his next project which was supposedly even bigger than his last. This time he had joined hands with movie mogul Subhash Ghai. But Trimurti (1995) was mired in trouble from the very beginning. The “mahurat” was held in Mumbai with Shah Rukh Khan, Jackie Shroff and Sanjay Dutt being touted as the star attractions of the film. But soon after, Sanjay Dutt was arrested in the Mumbai blast case. He had shot for a few scenes, but to avoid further damage to the film he had to be swiftly replaced with Anil Kapoor. But the end product didn’t come together. It had a bit of Mukul Anand and a bit of Subhash Ghai in it. Mukul’s villains never had the buffoonish quality Mohan Agashe’s Khokha Singh was infused with. The script was written and rewritten too many times, which resulted in a rather confusing output. And yet, Mukul’s inventiveness and his passion for spectacle shine through.

Advertisement

The one common strand that ran across all of Mukul Anand’s work, was the grandeur and scale of his cinematic vision.?There was finesse and style that he brought into his work while sticking to the Bollywood mainstream recipe. But he decided to pull out all the stops for Dus, his ultimate dream project, which he lived with for years. The plot revolved around terrorism in Kashmir, and he believed no one had ever attempted a mainstream political film of that magnitude. Salman Khan and Sanjay Dutt were to star along with Shilpa Shetty and Rahul Dev, who was making his debut with the film. Raveena Tandon was to feature in her first negative role as a terrorist named Nasheman. When he didn’t get permission to shoot in Kashmir, he moved to Salt Lake City, Utah, where the majority of the film was shot. But before he could complete his magnum opus, the 46-year-old Mukul Anand breathed his last. The man had too many ideas wiggling around in that head of his. But perhaps the Bollywood of the 80s and 90s was too minuscule, too small to contain all the ideas he had. It boggles the mind to think of what the man would have achieved with the advancement of technology and themes that Hindi cinema experienced, post-2000. Whatever little survives of Dus is a testament to this. Mukul Anand said in an interview to Suparn Verma way back in the mid-90s, “With Dus, I plan to usher a new way of thinking into commercial movies... You know what? I want to put up Dus on the Internet. Once the shooting starts we will create a site where people can debate the Indo-Pak issue"

Advertisement

-

Previous Story

Partition Museum: A Journey Through India’s Resilient Past And Hopeful Future

Partition Museum: A Journey Through India’s Resilient Past And Hopeful Future - Next Story