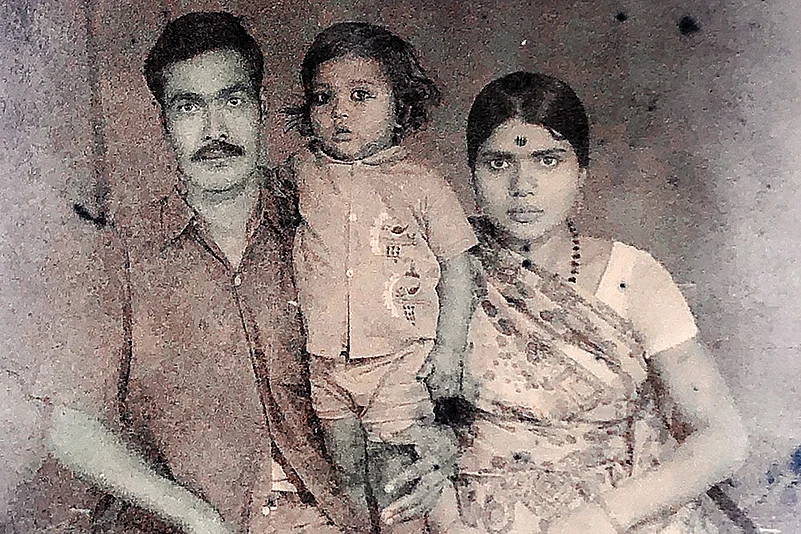

Father passed away, just the way he would leave the house every morning for the factory—quietly, without disturbing anyone.

Keeping Father Alive: Dealing With My Father's Death

Trying to make sense of the permanent void, attempting to find answers to the many unanswered questions, and striving hard to keep his memories breathing—how I am dealing with my father’s death

Everyone must leave this world one day. Yet, we yearn to fill the void, despite knowing well it can never be filled. Father was ill. He wanted to leave. We all wanted him to leave. But after he left, we felt incredibly empty. Everyone wanted me to come (from the US) after he died. For no reason. Is being a son reason enough? I came, but my arrival did not feel like coming. It felt very shallow and superficial. Yet, I did everything that was expected, and I went back; carrying with me an empty space and a heavy heart.

***

My paternal grandmother died many years ago and that’s when I came to know that people cry when someone dies. I did not cry. Rather, I was happy that she died. She used to beat up my mother. I vividly remember one of my brothers coming to school. It was the sports period and I was playing on the ground. My brother asked me to come home. “Grandmother is no more,” he said. I told him to go back home and that I would join him after the sports period. I had no sympathy for my grandmother.

After reaching home, I started eating grapes kept in the kitchen. My mother stopped me. I told her I was hungry. “Eat, but make sure no one sees you,” she said. I did not feel like looking at my grandmother the last time. I never liked her wrinkled face. Whenever I visited her in the village, she used to hug me tight and cry, making me feel awkward. I used to despise her wrinkles, but I loved my maternal grandmother’s wrinkles. I don’t have any explanation for this.

In her last years, my grandmother had developed blisters all over her body and puss oozed out of them. My brothers told me this. I never visited my grandmother in the hospital.

Her corpse burned slowly. “Since her body is wet, it is taking longer to burn,” someone said. This has stayed with me. I was sitting nearby and building a sandcastle. Later, I came to know that my English teacher, who was present during the last rites, told the class that Sushil (I) was a strange boy, who was busy building a sandcastle when his grandmother’s pyre was burning. Maybe, in the event of a death, it is necessary to show remorseful emotions. My father must have been sad. He might have cried silently, but never in front of us. Maybe his mother’s death left a void inside him. As for me, the removal of her cot from the house created some space for us to play and study, so I was glad.

***

We never saw our grandfather. My father, too, never saw his father. He died when my father was in his mother’s womb, we were told. It must have been difficult for my father to be a father because he did not have a father. Like the rest of the fathers of his generation, he did not interact much with his children. He used to love his eldest son a lot but could never express his feelings. And he would stop abruptly while expressing his love for the youngest one (me). I always sensed this, even as a child.

In his last days, my father did not have any desires. All he would say was that he was in pain And he missed his mother. A circle of life—that’s all I have been able to figure out.

I remember walking with him but he never let me hold his hand. Probably because he wanted to keep both his hands free to crush khaini (tobacco). Every year, he would promise to gift me a bicycle if I stood first in the class. But that never happened. Instead of a bicycle, I had to settle for a dosa and a bottle of Coca-Cola every year; the total price of which went up from Rs 6 to Rs 10 in all those years. When I was in the 9th grade, while having dosa and Coca-Cola at Rakesh Hotel, I, for the first time, realised that my father did not have enough money to buy a bicycle for himself, so I could not get one.

***

After I got a well-paying job, my father took voluntary retirement and went back to his village. The village where nobody accepted him. It took him 20 years to realise that the village was not for him. I entered this newfound village life very slowly. I wanted to connect more with my father than the village. I had seen him becoming quiet. I wanted him to talk to me. Once, he sheepishly told me that his shoes were torn. We went shopping, but he rejected the expensive ones, and settled for a pair of cloth shoes, saying: “These are absolutely fine.” I did not pay attention then, but later felt that he avoided buying better shoes looking at the price tag. When I asked my mother, she said: “Look at the bone protruding near his big toe. It hurts when he wears leather shoes, which is why he prefers cloth shoes.” It was for the first time I looked carefully at my father’s feet. He had been wearing the poor-quality leather shoes provided by his company all his life.

***

Two years ago, when I had been to my village to resolve a property issue, I saw our land for the first time. There were three-four pieces of fragmented land. Mango and bamboo trees were growing on a piece of land which had to be divided into three parts. The rest was in the name of my mother, which I had been trying to sell and deposit the money in the bank so that my parents could use it as and when required. There was another piece of land that remained submerged in water for four months. I had gone there with the purpose of selling that tract too. There were people ready to buy both the parcels. One of our relatives had erected a bamboo cane to claim the land. I removed this illegal occupation and struck a deal with a buyer. My father must have been very upset as he never wanted the land to be sold. As I was about to finalise the land deal, my father suddenly stood up in the veranda, staring into space. I found it strange. I asked him if there was a problem. After a long pause, he said: “Land should not be sold.” I looked helplessly at my mother.

***

He had not been keeping well for the past few years. When I met him six months ago, he was able to walk only with the help of a stick and could sit for a while. A paralytic attack affected his left side. But he was happy to see his grandchild. We left after a week and he again fell sick—never to leave the bed until his death.

We never used to talk on the phone anyway, but once bedridden, he almost lost his voice. One day, I asked my brother how much time my father had. He said, two or three days. I could not sleep that night. I was awake when I received the message: “Papa is no more.” I did not want to go. I had convinced my mother that a lot of money would be wasted if I came. But I could not stop myself. My arrival did not make a big difference though. By the time I reached, the last rites had been performed. One room was filled with goods meant to be donated in his memory and ration for the feast was kept in the other. The bed in the veranda, where papa stayed for six months, had also been removed. He was nowhere to be seen, neither physically nor in memories of that house.

He is no more. His memories are also scattered. I now have to put in some effort to picture his image. I try to search for answers to the questions I had asked him over the years—answers that now cannot be verified; answers that my father himself wasn’t sure of. He, for instance, did not know his birth date or year. He wasn’t sure when he left his village. “I ran away in 1958,” was his usual answer.

He came to Jadugoda in 1962, became permanent in his job in 1965. In 1976, he went to jail “because of Indira Gandhi.” By this, he meant the Emergency. He used to be angry with Gandhi. But, years later, when he came to Delhi, the only place he wished to see was the site where Gandhi was shot by her bodyguards. “But you never liked her,” I said. “It does not matter. She was a great leader,” he replied. He looked at the place carefully. He probably tried to connect the whole event and the place to his past experiences. He was silent.

Even in his last days, he did not have any desires. All he would say was that he was in pain. My mother said that in his last days, my father used to miss his mother. A circle of life—that’s all I have been able to figure out.

(Translated by Kaveri Mishra)

Jey Sushil is a writer and a journalist

This appeared in the print as 'Keeping Father Alive'